Dark streaks on a roof show up slowly, then one day they’re all you can see from the street. At that point, pressure washing starts to sound like a quick fix as it works wonders on driveways and sidewalks.

A roof, though, is built in layers, designed to shed water, not take a direct hit from it. Is Pressure Washing a Roof Bad?High-pressure spray removes surface growth, but it can strip protective granules, force water beneath shingles, and loosen materials that were never meant to be pushed from below.

Is Pressure washing a roof bad? Pressure washing promises instant results, and that can be tempting when time is tight or curb appeal feels urgent. The roof may look cleaner in a single afternoon, but that clean look can come at a cost that shows up later as leaks, repairs, or a roof that suddenly seems to age faster than it should.

At a glance, a roof looks solid and fixed in place, built to take on years of sun, rain, and wind without much complaint. However, roofing systems rely more on careful layering and surface protection than brute strength.

Water is meant to flow across the surface and move away quickly. When water arrives with force and direction it was never designed to handle, the behavior of the materials changes in subtle but important ways.

Pressure washing introduces energy that roofing materials do not normally face. Instead of gravity guiding water downward, the spray pushes laterally and upward, which alters how surfaces respond.

That force does not spread evenly. Concentrated streams strike small areas with enough impact to disturb materials that appear stable from the ground, especially along edges, overlaps, and seams.

On asphalt shingles, pressurized water can dislodge protective granules that shield the underlying asphalt from sunlight. Those granules do not grow back, and once they wash away, the exposed surface absorbs more heat and wears faster.

A roof succeeds because water stays on the outside. Pressure washing changes that balance by pushing moisture against laps, joints, and penetrations with enough strength to bypass natural barriers.

Once water slips beneath the surface, it follows paths that are hard to predict. Gravity no longer works in your favor once moisture reaches the underlayment or decking.

Insulation can absorb moisture unnoticed, wood can swell or soften, and fasteners can begin to corrode. By the time stains or leaks appear, the original cause often feels disconnected from the damage, which makes diagnosis harder and repairs more extensive.

The effects of high-pressure cleaning rarely look dramatic right away. A roof can appear cleaner and intact while small failures begin beneath the surface.

Those early changes tend to blend in with normal wear, which allows problems to progress without drawing attention. Granule loss can look like routine aging and lifted shingle edges may settle back into place after drying, even though their seal weakens.

Minor shifts in flashing may not show until heavy rain tests the system. Pressure washing does not always break a roof in a single moment, but it can shorten the margin of safety that keeps everything working as intended.

Roofing materials share a common purpose, but they behave very differently under stress. Each system relies on its own method of protection, attachment, and water control.

What works for one surface can create problems for another, especially when force replaces passive water flow. Some materials show damage quickly, while others hide it until weather and time expose weak points.

Asphalt shingles depend heavily on their outer layer to perform correctly. That top layer shields the asphalt core from heat and sunlight, which helps regulate aging and flexibility.

High-pressure spray can remove this protective layer unevenly. Granules wash away faster in some areas than others, which creates patchy exposure across the roof surface.

Once exposed, the asphalt beneath hardens more quickly, loses flexibility, and becomes more prone to cracking. Adhesive strips that help shingles stay sealed can also weaken, which increases the chance of wind lift.

Tile roofs appear rigid and substantial, but they rely on precise placement and balance rather than strength alone. Each tile rests in position as part of a larger system designed to shed water through overlap.

Pressure washing can introduce stress where tiles were never meant to flex. Small fractures can form without visible breakage, especially along edges and corners.

Individual tiles may shift slightly, which opens pathways for water beneath the surface. Once alignment changes, surrounding tiles can lose support, increasing the risk of broader issues over time.

Metal roofs handle weather well when their protective finishes remain intact. These coatings prevent corrosion and help regulate heat absorption across the surface.

Pressurized water can strip or thin those finishes, particularly along seams and fastener lines. Exposed metal reacts more quickly to moisture and air, which raises the chance of corrosion.

Fasteners may loosen under repeated force, and sealants around penetrations can degrade faster. The roof may still look sound, but its ability to resist water and temperature changes can decline.

Slate is dense and long-lasting, but it does not tolerate sudden impact or flexing. Each piece relies on its natural strength and precise placement to function correctly.

Pressure washing can introduce localized stress that leads to cracking or edge breakage. Damage may not appear immediately, as slate can fracture internally before visible failure occurs.

Once a slate breaks or shifts, surrounding pieces can lose support.

Stone-coated roofing combines a metal base with an adhered stone surface. That layered design depends on strong bonding between materials to remain effective.

Pressurized water can weaken that bond over time. Stone granules may release unevenly, and the underlying coating can wear away faster than intended.

As layers separate, the roof loses both protection and uniform performance.

Immediate results can create a sense of reassurance. A clean surface suggests progress, and the roof may appear refreshed from the street.

That visual change can mask deeper shifts that take place beneath the surface layers. Small disruptions caused by force tend to compound as weather cycles repeat, which allows minor issues to evolve into larger structural concerns.

Roofing systems rely on surface integrity to manage heat, moisture, and movement. When that surface loses consistency, the materials beneath work harder to perform the same function.

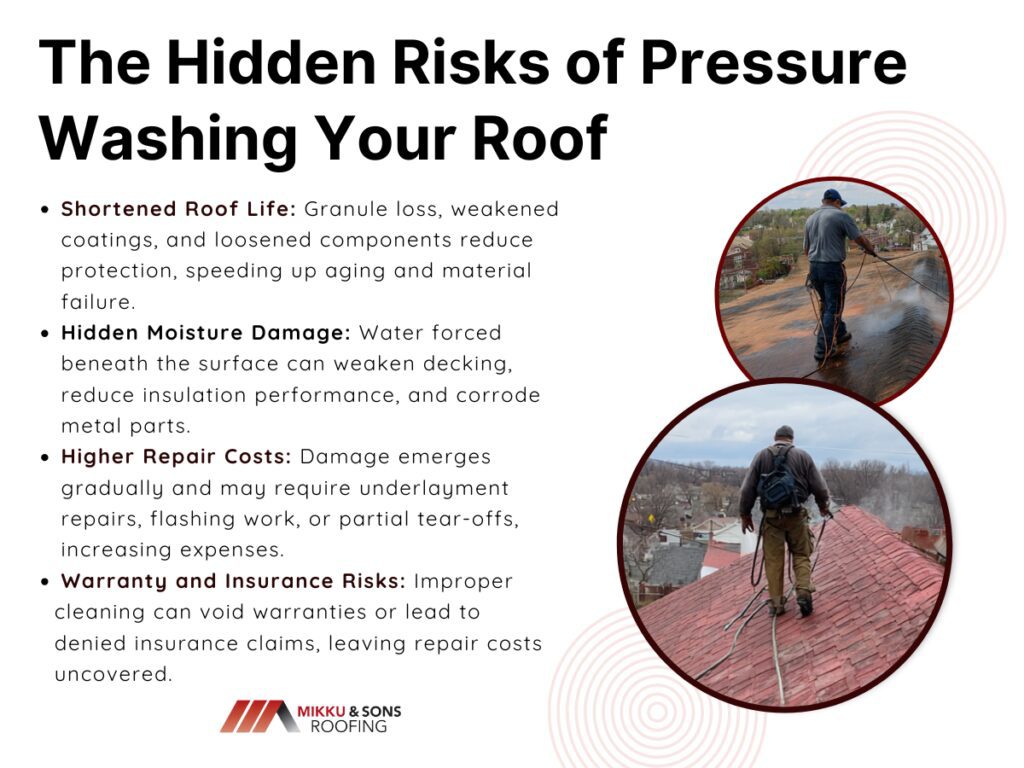

Granule loss, weakened coatings, and loosened components all reduce the margin that protects the roof from daily exposure. As that margin narrows, aging accelerates.

Shingles may stiffen sooner, sealants can fail earlier, and protective finishes can wear away at a faster pace than expected.

Moisture does not need a visible leak to cause harm. Small amounts that enter beneath the surface can linger, especially in shaded or insulated areas.

Wood decking can absorb that moisture and lose strength over time. Insulation may compress or lose effectiveness, which affects temperature control inside the building.

Metal components can corrode quietly, weakening connections long before rust becomes visible.

Damage related to pressure washing rarely points back to a single event. Problems surface gradually, which complicates inspection and diagnosis.

Repairs often involve more than surface fixes. Sections of underlayment may require replacement, flashing may need adjustment, and compromised materials can demand partial tear-offs.

Costs tend to rise because the original source of damage blends into normal wear, which delays corrective action.

Roof warranties and insurance policies rely on proper care and approved maintenance methods. Cleaning practices that fall outside those guidelines can shift responsibility.

Claims may face challenges when damage traces back to improper pressure use. Manufacturers and insurers can view that damage as avoidable, which leaves repair costs uncovered.

What began as routine maintenance can turn into an expense that offers no protection or recourse.

A roof stays in good condition when cleaning supports its original design. The safest methods focus on removing buildup without disturbing surface protection or forcing water where it does not belong.

Gentle cleaning methods address the root of discoloration and organic growth instead of relying on impact. This approach reduces risk across all roofing types and preserves the systems that keep water moving in the right direction.

Soft washing uses low water pressure combined with cleaning solutions to treat organic growth and stains.

The approach avoids mechanical stress and preserves the roof’s layers and coatings.

Specialized chemical cleaners focus on removing biological buildup without harming roofing materials.

They neutralize contaminants and work with water to create a safer cleaning process.

Localized growth often appears in valleys, shaded areas, or sections near overhanging branches.

Manual methods allow precise control and minimize risk to surrounding materials.

Rinsing is essential to complete the cleaning process, but it must follow the slope and natural drainage patterns of the roof.

Controlled water flow maintains the integrity of the system.

Cleaning a roof safely affects how well your roof continues to protect the space beneath it. When you maintain the surface carefully, you reduce the chance of leaks developing, and that can save a lot of stress and expense later.

A roof that stays intact with its layers and coatings preserved keeps water where it belongs, instead of letting it seep inside and cause damage. Leaks that reach the interior often reveal themselves through stains, damp insulation, or warped materials.

Addressing a roof from the outside with gentle cleaning methods helps prevent these issues before they ever appear indoors. At the same time, knowing how to fix a leaking roof from the inside gives you a backup plan if water manages to get through.