A foam roof seals gaps, adds insulation, and creates a single continuous surface without seams or fasteners. When it’s installed correctly and cared for, it handles heat, rain, and daily exposure better than many flat roofing systems.

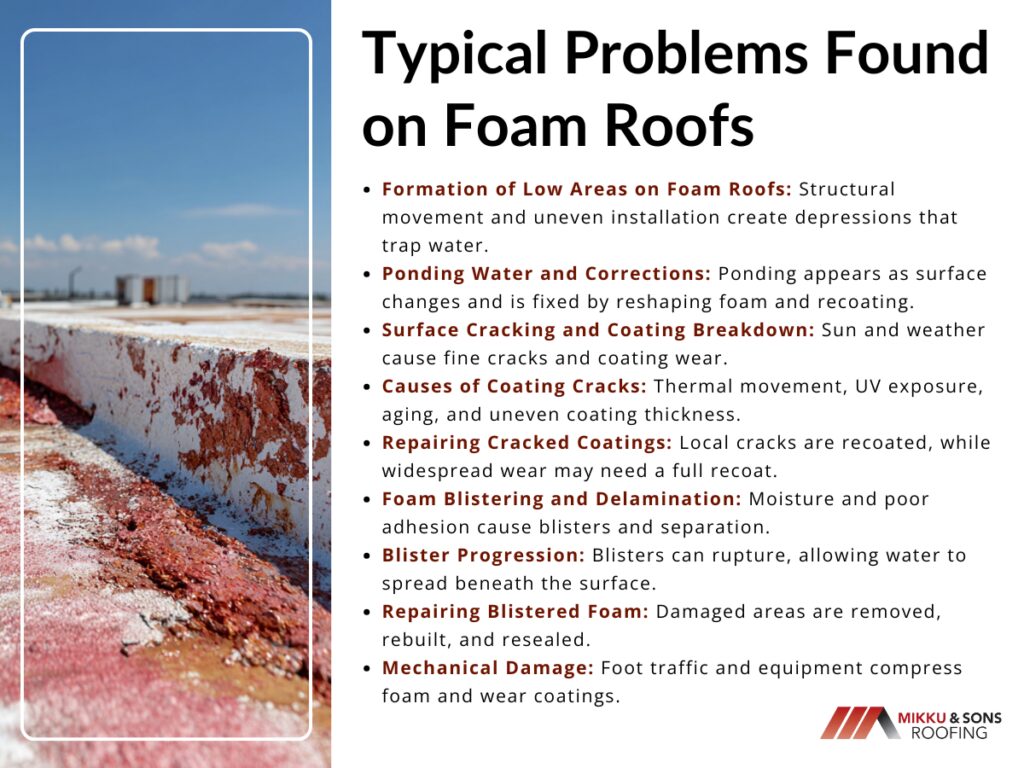

But like anything exposed to the elements year after year, it doesn’t stay perfect on its own. Problems with foam roofs tend to start small, a thin spot in the coating or a low area where water lingers longer than it should.

Water does not drip straight down the way it does with traditional systems. It can move sideways beneath the surface, spreading quietly before there’s any visible sign inside the building. Let's look at various common foam roof problems and how to fix them.

Spray foam roofing does not follow the same rules as most flat roof systems. Instead of layered sheets or membranes laid over a surface, this system forms directly in place.

That difference affects how the roof seals, insulates, and reacts to movement across the structure. Because the material expands and bonds to what sits beneath it, the roof becomes a single surface rather than a collection of parts.

A foam roof forms as a continuous layer that adheres to the deck, flashing areas, and penetrations in one pass. That seamless nature removes many of the weak points found in traditional flat roofs, especially around joints and transitions.

With no seams to pull apart, water entry tends to occur only where the surface has been damaged or worn thin. This changes the inspection process, since attention shifts from lap lines and fasteners to coating condition and foam integrity.

Foam bonds directly to the substrate rather than resting on it and roof penetrations receive the same material as the field area. This means leaks usually trace back to surface damage instead of joint failure

Most flat roof systems separate insulation and waterproofing into different components. Spray foam combines both functions into a single layer, which changes how heat and moisture move through the roof assembly.

Because insulation sits at the top of the roof rather than below a membrane, temperature swings affect the structure differently. This setup can reduce thermal movement in the deck, but it also places greater importance on surface protection.

Closed-cell foam resists water absorption as thermal performance comes from the roof surface itself. The coating condition directly affects both insulation and water resistance

Foam roofs allow repairs without removing large sections of material. New foam can bond to existing foam, which makes localized fixes possible without disturbing the rest of the system.

This repair method differs from membrane roofs, where patches often rely on adhesives or mechanical attachment. With foam, the goal focuses on restoring thickness and surface protection rather than replacing sheets.

Damaged areas can be cut out and refoamed making repairs integrated into the original surface. Large tear-offs are less common when problems are caught early.

Water that remains on a roof longer than expected changes how the entire system behaves. Foam reacts differently than sheet-based flat roofs because the surface coating carries much of the protective role.

When water stays in place, it places constant stress on that outer layer rather than shedding off naturally. There may be no immediate leak, no visible damage inside the building, and no obvious failure at first glance but the presence of standing water begins to affect performance.

Roof surfaces rarely remain perfectly flat over their full lifespan. Minor shifts in the structure, compression at the deck, or inconsistencies during installation can create shallow depressions that hold water after rainfall.

These low areas do not always appear dramatic. Even a slight variation in slope can trap water long enough to stress the coating system and expose weaknesses that would otherwise stay dormant.

Uneven foam thickness during installation, structural deflection in older buildings and settling around drains or penetrations can cause low areas on foam roofs.

Early indicators often appear on the roof surface long before water reaches the interior. Subtle changes in texture or color can signal that water has overstayed its welcome.

The roof surface itself usually needs adjustment so water no longer collects in the same areas. Repairs often involve reshaping the foam, restoring proper slope, and applying fresh protective coatings.

Ponding water may seem harmless at first, but on a foam roof it often signals a problem that grows with time. Addressing it early helps protect the coating system, preserve insulation performance, and reduce the risk of larger repairs later on.

The surface of a foam roof takes the brunt of daily exposure. Heat, sunlight, and weather cycles all work against the coating that protects the foam beneath.

Over time, that constant exposure can show itself through small surface changes that are easy to overlook at first. These issues usually appear as fine cracks or worn areas that seem cosmetic.

Coatings expand and contract as temperatures rise and fall. Repeated movement, combined with aging materials, can lead to surface cracking, especially in areas that receive intense sunlight or experience wide temperature swings.

Application thickness also plays a role. Coatings applied too thin wear faster, while uneven coverage can create stress points that crack sooner than surrounding areas.

Daily thermal expansion and contraction, prolonged UV exposure and inconsistent coating thickness all cause coatings to crack over time.

Repairs focus on restoring the protective barrier rather than replacing the entire roof. Localized cracks often receive cleaning, sealing, and recoating to rebuild thickness and flexibility.

Widespread breakdown may call for a full recoat to reestablish uniform protection. Addressing cracks early can limit repairs to surface work and extend the service life of the foam system.

Surface cracking and coating breakdown serve as early warnings rather than sudden failures. Paying attention to these signs allows timely repairs that protect the foam beneath and keep larger problems from developing.

Blistering and separation occur when the bond between the foam, the substrate, or the coating begins to fail. Once that pressure has nowhere to go, it forces the material upward, creating raised areas that weaken the roof’s protective layer.

This type of damage often signals a deeper issue rather than surface wear alone. Trapped moisture, poor adhesion, or contaminated substrates usually sit at the root of the problem.

Once a blister forms, the surrounding area becomes more vulnerable. Movement from foot traffic or temperature shifts can cause the blister to rupture, allowing water direct access to the foam beneath.

Delamination occurs when the foam or coating loses adhesion across a wider area. At that point, water can travel beneath the surface rather than draining off, which accelerates deterioration beyond the original blister.

Raised or spongy areas underfoot often provide the first clue. In some cases, the coating may appear stretched or slightly discolored where separation has begun.

Repairs start with cutting out the affected section to expose the underlying condition. Any damp or loose material must be removed so new foam can bond properly.

After rebuilding the area with fresh foam, the surface receives a protective coating that ties the repair back into the surrounding roof. When moisture sources get addressed at the same time, these repairs tend to hold up well over the long term.

Foam roofs handle exposure well, but they do not respond the same way to repeated physical stress. Unlike hard membrane systems, foam can compress under weight, especially in areas that see regular movement or support equipment.

Over time, that compression changes the surface profile and weakens the protective coating. A single step rarely causes noticeable harm, but repeated pressure in the same locations creates wear patterns that eventually break through the coating and expose the foam.

Walking paths often form naturally between access points, HVAC units, and roof edges. When these paths lack added protection, the foam beneath the coating can compress and lose thickness.

As the foam compresses, the coating stretches and thins. That loss of uniform coverage makes the surface more prone to cracking and moisture entry.

Mechanical units place constant load on the roof surface. Vibration from fans or compressors adds stress that foam roofs do not absorb as well without reinforcement.

Designated walk pads and reinforced pathways help distribute weight and reduce surface wear. These additions protect the foam while allowing safe access for maintenance and inspections.

When traffic routes are planned and protected, the roof surface maintains its integrity longer and repair needs decrease. Mechanical damage often develops in predictable locations.

Managing traffic and equipment loads plays a key role in preserving foam roof performance and avoiding premature surface failure.

Sun exposure plays a major role in how long a foam roof lasts. The foam itself does not tolerate direct ultraviolet light, which is why a protective coating covers the surface from day one.

When that coating thins or wears away, the foam beneath begins to change. This type of deterioration progresses slowly, often without obvious signs until the foam surface starts to powder or erode.

Exposed foam reacts quickly to sunlight. The surface can discolor, become brittle, and lose density as ultraviolet rays break down the material.

Once erosion begins, water can cling to the roughened surface rather than draining away. This combination of moisture and sun exposure accelerates surface loss and increases the chance of leaks.

The coating serves as both a UV shield and a weather barrier. Areas with thin or uneven coverage wear faster, especially on roofs that receive full sun throughout the day.

Powdering, surface roughness, or visible foam color changes point to UV damage. These signs usually appear before leaks develop, which creates an opportunity for corrective work.

Repairs typically involve cleaning the affected surface, rebuilding lost foam where necessary, and applying a fresh protective coating. Restoring proper thickness returns the roof’s ability to resist sunlight and shed water.

Regular recoating remains one of the most effective ways to slow UV-related deterioration and preserve foam roof performance. UV exposure remains a constant factor for foam roofs. Maintaining the protective coating helps prevent surface erosion and keeps the system functioning as intended.

Foam roofs operate differently from traditional flat roofing systems, and the way they handle water, heat, and physical stress affects both performance and maintenance. Knowing the types of problems to watch for allows you to prioritize inspections and respond before small issues evolve into larger failures.

Comparing foam roofing to conventional systems emphasizes these differences. Unlike built-up, single-ply, or modified bitumen roofs, foam integrates insulation and waterproofing into one layer.

That integration changes where problems appear and how they are repaired. Issues that would normally show up at seams or fasteners in traditional roofs instead emerge on the foam surface, making coatings, thickness, and adhesion critical factors.